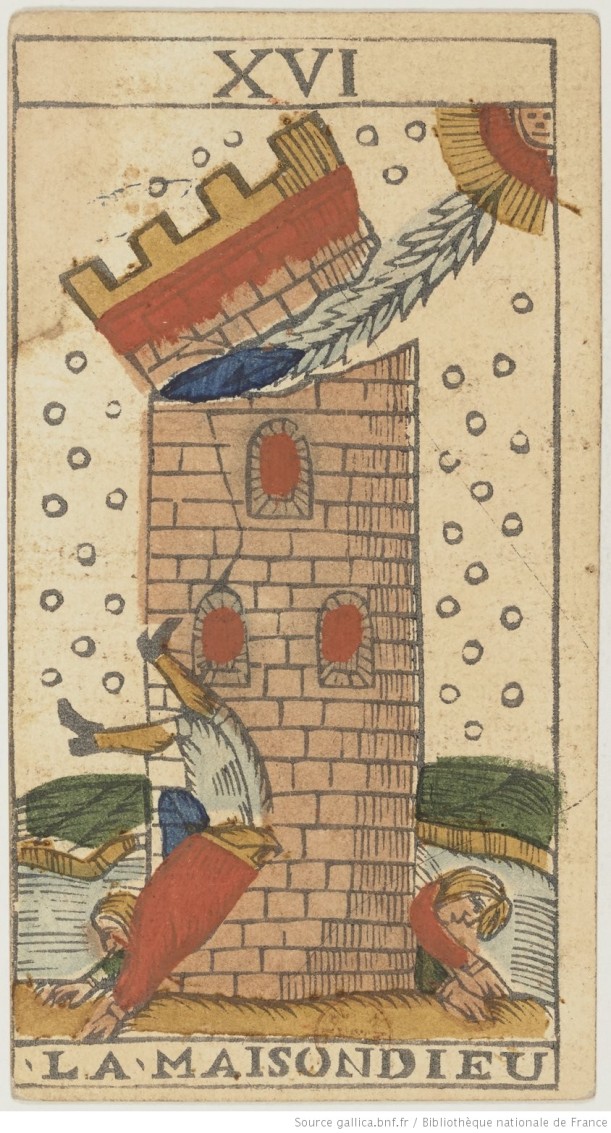

The Isis of the Tarot, or the Birth of a Myth

Monique Streiff Moretti

Translator’s Introduction

“A subterranean current is awakened by the growing prestige of an unknown civilisation to become a genuine obsession. Begun in a mixture of folk and classical traditions, the Egyptian tale takes shape and develops beneath the sign of erudition. All the ancient and modern writings, unknown authors, are all gathered and methodically commented, to which are added exegeses and scholia. An archaeology and an iconography of monuments, whether authentic, imaginary or false, linguistic, ethnological and scientific systems are all set to the task. It is a baroque architecture in the making to the glory of a fantastic Egypt. The legend of a myth, which was itself a work of poetry and a novel, often reaches the domains of the absurd, and evolves in the impossible. This is why the mythographers of our time have generally excluded it from the fields of their preoccupations, or neglected it.”

– Jurgis Baltrušaitis, La Quête d’Isis, Flammarion, p.13.

Statue of Isis

The phenomenon known as “Egyptomania” is the subject of a growing body of literature, from various points of view, from among which the interested reader may consult the following general works: Bob Brier, Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs, St. Martin’s Press, 2013; Ronald H. Fritze, Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy, Reaktion Books, 2016; James Stevens Curl, Egyptomania: The Egyptian Revival, a Recurring Theme in the History of Taste, Manchester University Press, 1994; or the following articles: Claudia Gyss, “The Roots of Egyptomania and Orientalism: From The Renaissance to the Nineteenth Century,” in Desmond Hosford et Chong J. Wojtkowski eds., French Orientalism: Culture, Politics, and the Imagined Other, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010 [pp.106-123]; Jean-Marcel Humbert, “Egyptomania”, in Michel Delon (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment, vol. 1: A-L, Routledge, 2001, or Antoine Faivre’s entry in the Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism, s.v. ‘Egyptomany,’ Brill, 2005. On the subject of the hieroglyphs and their study, one may profitably consult The Myth of Egypt and Its Hieroglyphs in European Tradition by Erik Iversen, Princeton University Press, 1993. More directly relevant to our subject is Erik Hornung’s The Secret Lore of Egypt, Cornell University Press, 2001. For a scholarly translation and analysis of the myth of Isis and Osiris, see the works Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride (1970) and The Origins of Osiris and his Cult (1980) by J. Gwyn Griffiths. Incidentally, Isis Studies is a growing academic discipline in its own right, with a concomitant body of literature.

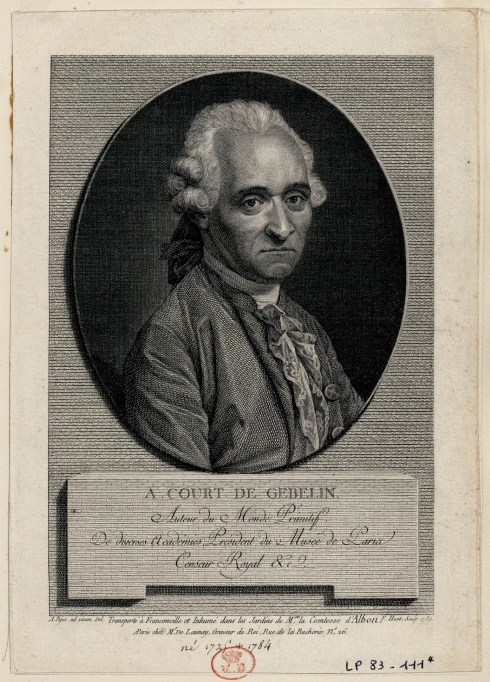

The study of the influence of this Egyptomania on the Tarot, its iconography and its historiography, has not escaped the attention of scholars, and there are now a number of works dealing with this aspect of Tarot history and myth in some depth. A Cultural History of Tarot (2009) by Helen Farley is one such example. Unfortunately, this work is very uneven and marred by all manner of mistakes. One example, not to labour the point, is that the crude illustrations in volume 8 of Court de Gébelin’s Le Monde Primitif are attributable – “probably” – to … Jean-Marie Lhôte! No one would be more surprised to learn this than the man himself, still among us, at over 94 years of age, although he would no doubt be delighted at this circular turn of events, he himself being responsible for identifying the artist, one Mademoiselle Linot. The article Out of Africa: Tarot‟s Fascination With Egypt by the same author is little more than a descriptive and uncritical list of dates, names and books, without any serious analysis, although it may be useful as a reference timeline.

For an in-depth examination of the origins and development of the so-called “occult Tarot,” one must turn to A Wicked Pack of Cards. The Origins of the Occult Tarot, by Ronald Decker, Thierry Depaulis, and Michael Dummett, Duckworth, 2002; and for a fairly comprehensive overview of the general background and later fortune of this “occult Tarot”, A History of the Occult Tarot by Michael Dummett and Ronald Decker, Duckworth, 2002. These two books, along with Dummett’s groundbreaking The Game of Tarot (1980), may be considered the fundamental works on the subject in English, although they very much focus on the personalities behind the writings on the occult Tarot rather than on the milieu that gave rise to them. Typically, works on the subject tend to focus on the Renaissance and the hermeticising or neo-Platonic circles of the time, rather than on the more pertinent developments of the Enlightenment, most notably Freemasonry.

The book by the Egyptologist, Erik Hornung, The Secret Lore of Egypt, Cornell University Press, 2001, is perhaps the work that comes closest to providing the most comprehensive examination of the Egyptian question from the point of view of cultural and intellectual history. However, despite containing one chapter devoted to Freemasonry and another to the Tarot, only one line in each mentions the subject of the present article: Court de Gébelin’s singular and seminal contribution, the two essays on the Tarot found in the eighth volume of his Monde primitif analysé et comparé avec le monde moderne [“The Primeval World, Analyzed and Compared to the Modern World”], published in 1781. The chapter on Freemasonry provides insight into the early Egyptian-inspired Masonic rites and regimes, but otherwise focuses on the figure of Cagliostro, while the chapter on Tarot focuses on later periods, from the Parisian occultists of the Belle Époque and the Theosophical Society to more recent developments. This is all the more regrettable in that Baltrušaitis’ earlier work, cited in epigraph, also lacks a chapter on the subject, as the author of the following piece notes.

A more recent work, Napoleon’s Sorcerers, by art historian Darius Spieth, sheds light on the murky world of the Sophisians, an obscure sect of para-Masonic origin, who had concrete links to Egypt by way of Napoleon’s military campaign in that country (1798-1801). Although that work does not mention the Tarot, and the society in question in fact very slightly post-dates Court de Gébelin’s work, it provides extensive insight into the origins, members, activities and goals of a contemporaneous secret society entirely taken by the myth of Egyptian wisdom. One must bear in mind, in this respect, that the theory of the supposed Egyptian origins of the Tarot is coterminous to that which imputes the same origins to Freemasonry, as well as to the elaboration of the first rites of so-called Egyptian Masonry by the adventurer known as Cagliostro, which we may now date to 1781. (Leaving aside putative predecessors, information on which is scarce and subject to caution, and which will be the subject of a future essay.) Egyptologist Florence Quentin summarises the issue by saying: “The egyptomania of the 18th century and the beginnings of Masonry were contemporaneous, they mingled all the more easily in that the role of religion and its institutions were then being debated.” (Isis l’Eternelle, Albin Michel 2021, p. 187) On the links between Freemasonry and Egypt, whether real or imaginary, one will consult the book by Barbara De Poli, Freemasonry and the Orient: Esotericisms between the East and the West, 2019, especially chapters 1-3.

This is by no means an exhaustive, or even a critical bibliography. One of the most fundamental works on the subject remains unavailable in English translation, La Quête d’Isis by the Lithuanian art historian Jurgis Baltrušaitis. Similarly, an accurate and scholarly edition of Court de Gébelin’s 40-odd pages on the Tarot in English is as yet a major desideratum, despite an annotated edition by one of the leading scholars being available in French for four decades. The translations of the essays by Court and de Mellet by the polemicist Jess Karlin (pseudonym of Glenn F. Wright) in his Rhapsodies of the Bizarre, and the very recent publication of Donald Tyson’s Essential Tarot Writings, go some way to address this lacuna, and generous excerpts are provided in the works by Dummett et al. listed above, to which we may add the new translations by David Vine and Dantzel Cenatiempo. We have already noted that a period manuscript translation by General Rainsford has also been digitised. This is to say that, despite this profusion of works on the subject, there is very little to definitively give the lie to Baltrušaitis as quoted above.

The context provided by works such as those listed above, and especially, those by Lhôte , Hornung, Spieth, and Baltrušaitis, to which we may also add the 2 volumes of Auguste Viatte’s Les sources occultes du romantisme (1928), sheds much-needed light on the manner in which what may now appear as merely “bad history,” conjectural speculation tarted up as fact, or even deliberate mystification, managed to mask itself to later generations of researchers and historians, with the predictable result that it would be first assigned – faute de mieux – to history, and later, written off by mainstream scholars as pertaining to the domain of fiction – rather than being dealt with, as it behoves, as an attempt at historiography, or a fortiori, mythography.

Knowledge of this context is crucial in order to arrive at a critical understanding of the accumulated elucubrations of almost two and half centuries of Tarot literature, which is the point of the following article, the signal importance of which consists in, not in the mere lining up of a series of facts and conjectures, but in interpreting the facts such as they are known, with close reference to the primary text, the sources upon which the author drew for its elaboration, its presiding ideas and thrust, as well as the uses to which it was put. That is to say that it conclusively demonstrates Court de Gébelin’s writings as being the articulation of the founding myth of the occult Tarot.

Portrait of Court de Gébelin

One major flaw in the existing Tarot literature, whether popular or scholarly, has been to neglect to examine Court’s writings on the Tarot within the context of his greater body of work, a most unfortunate omission. Added to this, taking his speculations on the Tarot at face value, or by the same token, rejecting them outright, has also resulted in some equally unfortunate misunderstandings. The purpose of publishing this translation is to present a more nuanced view of the origins of the so-called occult Tarot, and to provide further indications which the interested reader may choose to pursue.

Bucking the trend, mention must be made, once again, of Dummett, Decker and Depaulis, who call Le Monde Primitif “a monument to misdirected erudition” (op. cit. p. 56), an assessment that is harsh but fair, though, as we shall see, it is perhaps the latter who are misdirected as to the true intent of the work. In any event, A Wicked Pack of Cards (pp. 56-57) gives a very brief overview of the work and its content. For a comprehensive summary of the thought of Court de Gébelin in English, one must consult F. E. Manuel’s ’The Great Order of Court de Gébelin’ in the work The Eighteenth-Century Confronts the Gods, Harvard University Press, 1959. Ronald Grimsley’s From Montesquieu to Laclos: Studies on the French Enlightenment (Droz, 1974, pp. 23-26) provides a good summary of Court’s ideas, although citations are left untranslated. We have adapted his opening summary and translated the citations into English.

“Convinced of the universality of language, he proposed to seek “the analogy of all languages,” which were ultimately to be reduced to a single form – “the primitive language bestowed by nature.” More especially, he insisted on the idea of a universal order and harmony in which every particular element had its appointed place. Language therefore, was not the result of mere chance but followed the universal rule that “everything has a cause and a reason.” Moreover, since the spoken word is given by nature herself, “nature alone can guide us in the search for all she has produced, and alone can explain the wonders of speech.” Gébelin believed that with “nature” and “primitive religion” as his guide, he could make an illuminating philological study of ancient religion, mythology and history.”

Another reason Court’s work has been systematically overlooked in the Tarot world is the fact that, by and large, the only sustained attention it has received has been in largely unpublished doctoral theses, unavailable to the general reader, and treating of philology, linguistics and seemingly unrelated specialised subjects. Let us cite a couple, for the enterprising reader: Joseph George Reish, Antoine Court de Gébelin, Eighteenth-Century Thinker and Linguist. An Appraisal, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1972; William Henry Alexander, Antoine Court de Gébelin and his Monde Primitive, Stanford, 1974. For more accessible analyses of this dense work, one must consult Gérard Genette’s ‘Generalized Hieroglyphics’ in Mimologics, University of Nebraska Press, 1995; and especially, Anne-Marie Mercier-Faivre’s important body of work, notably, ‘Le Monde primitif d’Antoine Court de Gébelin, ou le rêve d’une encyclopédie solitaire,’ ‘Antoine Court de Gébelin et le mythe des origines,’ in Porset and Révauger, Franc-maçonnerie et religions dans l’Europe des Lumières, Champion, 1988; ‘Le Langage d’Images de Court de Gébelin’ in Politica Hermetica vol. 11, 1997; Un supplément à « l’Encyclopédie » : le «Monde Primitif» d ‘Antoine Court de Gébelin, suivi d’une édition du « Génie allégorique et symbolique de l’Antiquité », extrait du «Monde Primitif» (1773), Champion, 1999; and, in English, her biographical entry on Court in the Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Brill, 2005. Above all, let us cite the crucial essay by Dan Edelstein, “The Egyptian French Revolution: antiquarianism, Freemasonry and the mythology of nature,” in Dan Edelstein ed., Super-Enlightenment: Daring to Know Too Much, Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 215-241.

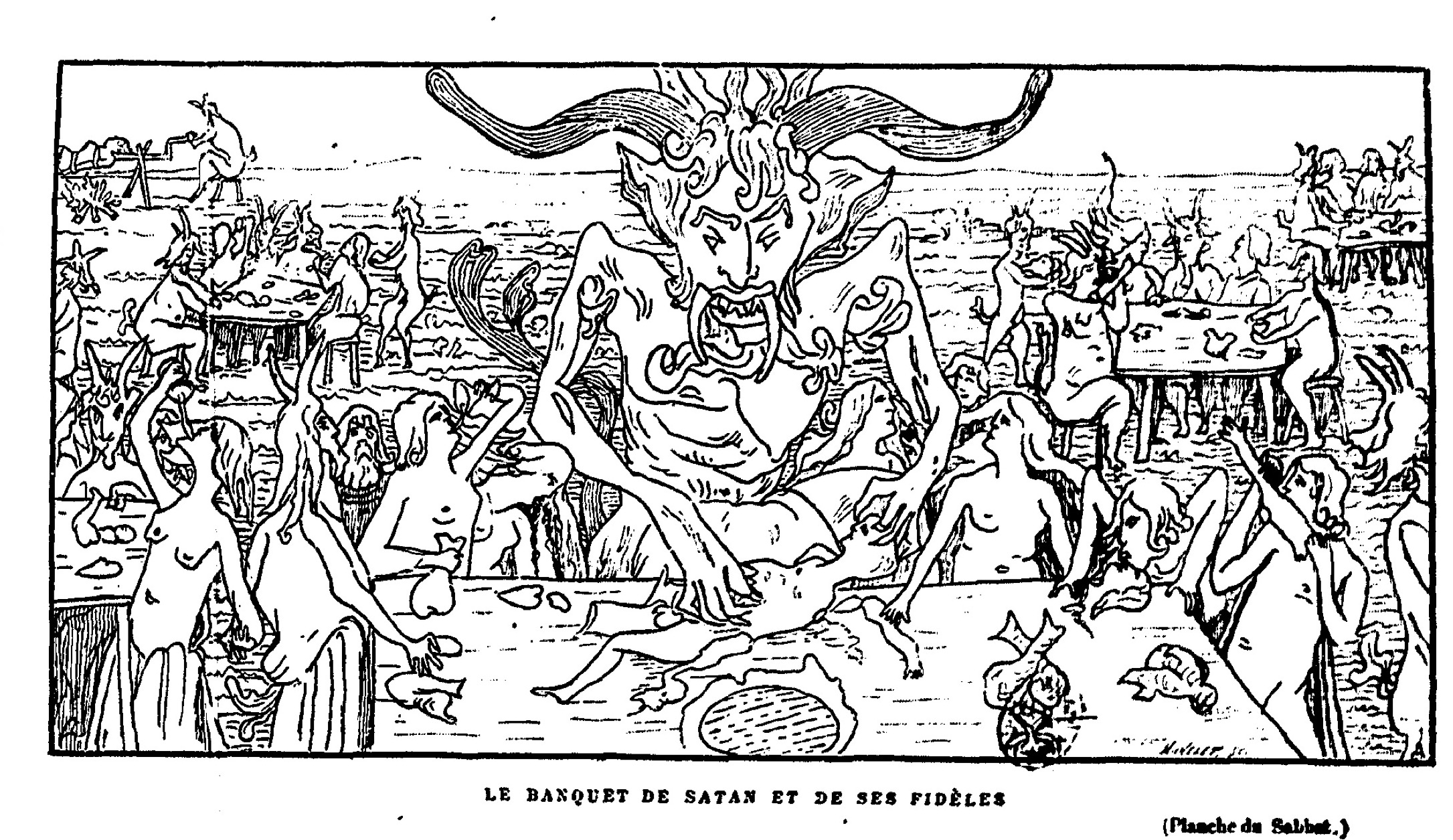

The idea that secular Masonic ideals sought to replace Christian values is one dear to Catholic apologists, repentant (or unabashed) Freemasons and conspiracy theorists of all stripes, beginning with Barruel’s Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire du Jacobinisme in 1797-1798, Cadet de Gassicourt’s Le Tombeau de Jacques de Molay, ou Histoire secrète et abrégée des initiés anciens et modernes, templiers, francs-maçons, illuminés, 1796-1797, and John Robison’s Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, carried on in the Secret Meetings of Free-Masons, Illuminati and Reading Societies, 1798, to name but a few. Although this theory of the Masonic origins of the French Revolution has been disproved in its particulars, there is nonetheless a certain commonality of purpose among these movements and societies that must be examined, pace Albert Soboul and his La franc-maçonnerie et la Révolution française, as shown by Charles Porset in his Hiram Sans‑Culotte ? Franc-maçonnerie, Lumières et Révolution (Honoré Champion, 1998). This is equally true of what may be called the “myth of Egypt” and its contribution to Enlightenment or revolutionary ideals, a contribution detailed in the article by Michel Malaise, La révolution française et l’Égypte ancienne.

This is also the view of mainstream scholars, such as Claudia Gyss, who writes that: “Concurrent with the evolution of views on Egypt from the fantastic to the scientific and Orientalism, Egyptian art also served political functions. […] Egyptian art became an instrument of propaganda, and antiquity became the object of a true cult.” (op. cit., p. 116.) Similarly, Florence Quentin notes that: “All these fables (which relate, as we have seen, to egyptomania) will fuel a revolutionary movement which will seek to emancipate itself from Christian authority by attempting to establish a syncretism which would unify all the cults of humanity. … In its effort to struggle against Christianity all the while opening up other symbolic and religious (in the sense of religare, “to bind”) fields, the Revolution will in its turn make use of Isis.” (Isis l’Eternelle, Albin Michel 2021, pp. 176/191) Dame Frances Yates notes that, “The cult of a Supreme Being, using Egyptian symbols, was the religion of the Revolution.” Baltrušaitis, for his part, states that: “The Revolution combatted the Church by reanimating the Egyptian divinities” (op. cit. p. 46); “Egyptian theogony became a instrument of atheism, and at the same time, a temptation, and a secret belief” (p. 79); and “Egypt is no longer a myth that rubs shoulders with the Old Testament and which is elevated by the vision of the Gospels, which it prefigures. The Egyptian myth now serves to dismantle Christianity, reduced to the category of a primitive religion. […] Every anti-religious struggle ends in religion. It is less the destruction of one cult than its replacement by another. Christianity being, for the theoreticians of sidereal dogmas, a later, disfigured form of the first theogony of man, the truth is reestablished in a return to the origins. […] A Freemasonic fantasy? Perhaps… but beneath the signs of the times, for all the promoters of these intellectual systems, from Court de Gébelin to Lenoir were Freemasons.” (pp. 307-308.) As far as Court is concerned, as Baltrušaitis says, “by his encyclopaedic spirit and his liberalism, he belongs to the line of philosophers and economists who prepared the Revolution.” (op. cit. p. 28.) Frances Yates will not say otherwise: “Gébelin died before the outbreak of the Revolution but he held an important position in the intellectual world of liberals and philosophes which was moving toward it.” (op. cit.)

Edelstein cogently notes:

“There were two crucial links connecting Revolutionary culture and ancient Egypt. First, Freemasonry had made Egyptian mythology both respectable and popular; in the hands of Antoine Court de Gébelin, it even became the vehicle of the true, original religion of humanity.” (Edelstein, op. cit., p. 216)

“… If the golden age really had existed in Egypt, and was not just as poetic fiction, then it could conceivably serve as the model for future social and political transformation.” (ibid. p. 217)

“Through the medium of Antoine Court de Gébelin, Masonry’s appropriation of Egyptian culture helped redeem the maligned body of pagan mythology. Court de Gébelin accomplished this feat in his multi-volume Monde primitif, a gargantuan study of the language, beliefs, social structure and scientific knowledge of a vaguely defined primitive world, but one which was closely associated with Egypt. (ibid. p.220)

“Not only did he there portray the monde primitif as an embodiment of Masonic social ideals, but he used Masonic symbolism to decipher the mysteries of ancient myths. (ibid. p.221)

The peculiarly mythographic type of subversive undertaking would be further developed by Charles-François Dupuis in his ambitious Origine de tous les Cultes, ou la Réligion Universelle, published in 1795 to Masonic acclaim. Incidentally, Dupuis’ work also allegedly contributed to spark Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign – yet another Egyptian connection, although the political, military and commercial reasons for the campaign remain much more prosaic. (On the Egyptian Campaign, see Napoleon in Egypt by Paul Strathern, Napoleon’s Egypt by Juan Cole, Bonaparte in Egypt by J. Christopher Herold, and Mirage: Napoleon’s Scientists and the Unveiling of Egypt by Nina Burleigh. On Freemasonry and the Egyptian expedition, see Les francs-maçons de l’Expédition d’Egypte by Alain Quéruel.) Dupuis, writing in the Revolutionary era, was able to go further than Court had in his critical interpretation of religion and myth. Dupuis, “disciple of the astronomer and Freemason Lalande and successor of Court de Gébelin, is frequently quoted with approval in the freemasonic writings. He also thinks that the base of all religions is exactly the same. It is simply sun-worship, or the worship of nature or the generative forces, born in Egypt. The various fables and myths, including Christianity, are but astronomical allegories, of which the most recent are the most bizarre. In effect, the dominant idea of his Origin of All Religious Worship is that Christianity is but a fiction or an error, a sequence of allegories copied on the sacred fictions of the Orientals. Even more critical than Court de Gébelin, Dupuis describes religions as diseases to be eliminated.” (Helena Rosenblatt, ‘Nouvelles perspectives sur De la religion: Benjamin Constant et la Franc-maçonnerie’, Annales Benjamin Constant, N° 23-24, 2000, p. 146.) F. E. Manuel sums up the nature of their works accurately when he states that, “The writings of Court de Gébelin and Dupuis … are memorable more for their influence – like the revolutionary oratory they resemble – than for their intrinsic worth …” (op. cit. p. 249) Dupuis’ lasting contribution to religious studies, in one way or another, will have been the elaboration of the controversial ‘Christ Myth‘ theory.

Another eminent Freemason and Egyptianising savant, Alexandre Lenoir, would also follow more or less directly in Court’s footsteps, elevating the myth of Egypt to ever more dizzying heights in his work La franche-maçonnerie rendue à sa véritable origine, and in his numerous other works of Egyptology. The works of Freemasons such as Nicolas de Bonneville, Lenoir, Ragon, and the other successors of Court explicitly outline the perceived elective affinities between the hieratic initiatory institutions of ancient Egypt, on the one hand, and the progressive and equally initiatory Masonic values on the other. Rosenblatt (op. cit., pp. 148-149) provides entire pages of relevant – and highly telling – quotations, which only serve to highlight the fundamental and inherent contradiction between the elitist, esoteric, nature of Freemasonry, and its professed egalitarianism and rationalism. This paradox forms the basis for the detailed article by Michel Malaise, La révolution française et l’Égypte ancienne. Another contradiction, symbolic this time, is further underlined by Hornung when he notes that the orientation of the modern Masonic myth of Egypt “is not toward the “Beautiful West” of the ancient Egyptian afterlife but rather toward the “Eternal East.”” (op. cit., p. 127.)

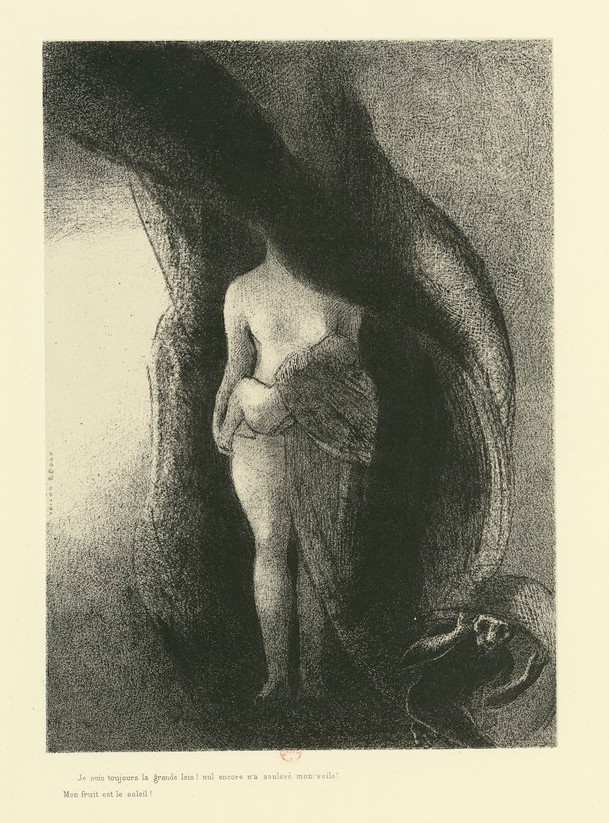

Je suis toujours la grande Isis! Nul n’a encore soulevé mon voile! – Odilon Redon, 1896.

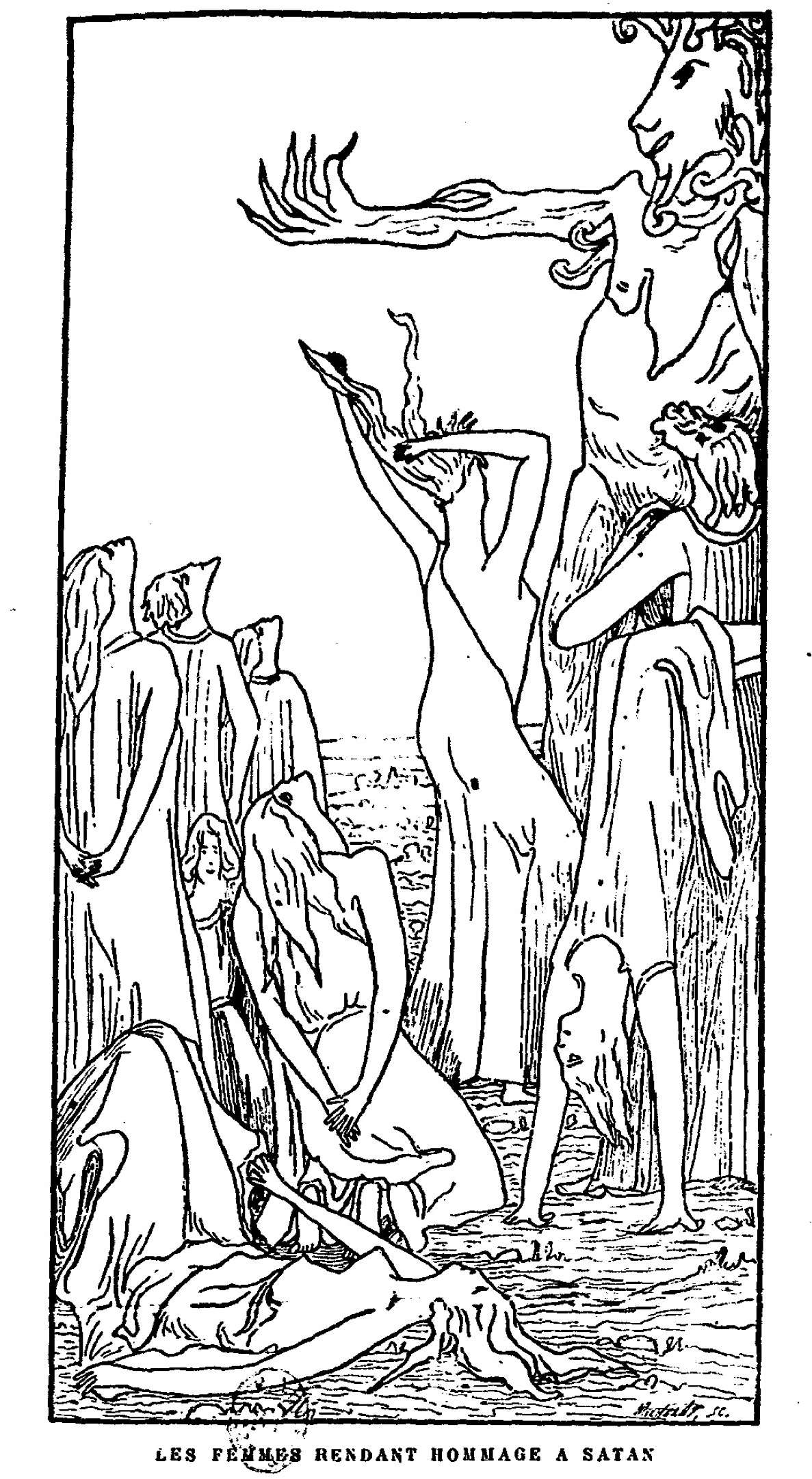

As Dame Frances Yates noted in her review of Sir Michael Dummett’s book, “The role of Freemasonry, with its Hermetic-Egyptian rituals, is a force very much to be reckoned with in all this movement.” (In the Cards, New York Review of Books, February 19, 1981.) Further examining the matter, Jean-Marcel Humbert says that, “The ties uniting Freemasonry – which officially drew its vital strength from the sources of ancient Egypt – to Isis are of course very close, as with Egyptomania in general.” (Jean-Marcel Humbert, ‘Les nouveaux mystères d’Isis, ou les avatars d’un mythe du XVIe au XXe siècle,’ in L. Bricault ed. De Memphis à Rome, 2000, p. 171) And as the Masonic historian Gérard Galtier states, “There exists, thus […] a revolutionary element in the Egyptian Rites which is their spiritual reference and their desire for an attachment to a non-Christian tradition. Note that during the Revolution itself, the Egyptian influence affected the revolutionary cults, such as that devoted to the goddess Reason.” (Gérard Galtier, ‘L’époque révolutionnaire et le retour aux Mystères antiques : la naissance des rites égyptiens de la maçonnerie,’ in Politica Hermetica n°3, « Gnostiques et mystiques autour de la Révolution française », 1989, p. 124)

The question then arises as to how and why the Freemasons of the late 18th century became associated in such an enterprise, namely, the reanimation of an Egyptian deity, to use Baltrušaitis’s terms, when many of them were in fact devout Christians, whether Catholic or Protestant, and in some cases, churchmen themselves. One must bear in mind that the anti-clericalism associated with French Freemasonry only took off in earnest from the mid-nineteenth century. The schism within Freemasonry, resulting in the so-called Anglo-Saxon and Continental traditions, dates to 1869, then 1877, when the split was fully consummated on account of the French Grand Orient removing the need for candidates to profess a theistic belief. This answer to this question lies both at the periphery, and paradoxically, at the heart of the matter.

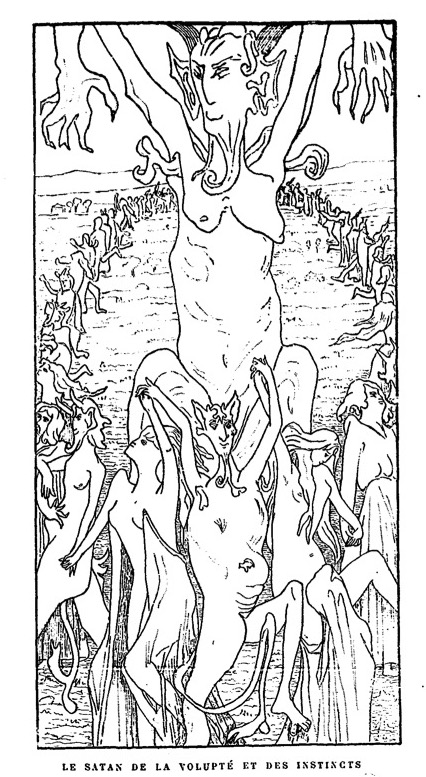

One may surmise that perceived deeper affinities between religions of antiquity and the Christian faith led to a certain Masonic form of perennialism, following which the outward religious form was considered but a simulacrum; changeable, replaceable, and ultimately disposable. This notion of elective affinities between Freemasonry and the reanimated goddess, so to speak, or so-called Goddess worship, has even led some to think that the phenomenon was a conscious and deliberate one. See, for example, the decidedly unscholarly but nonetheless interesting work by William Bond, Freemasonry And The Hidden Goddess, which elaborates considerably on this point. The feminist egyptologist Florence Quentin, for her part, will state that: “In Masonry, the goddess always appears beneath the surface, as though it were impossible to get rid of the feminine from every initiation or authentic spiritual path, were they “reserved” to circles of men… […] It is difficult, as we see, in a period in which the Convention has overthrown the dominant religion, to escape symbolisation (which has been definitively shown to structure society), especially if it takes the shape of the universal Great Mother…” (Isis l’Eternelle, Albin Michel 2021, p. 189) The article by Jean-Marcel Humbert, ‘Les nouveaux mystères d’Isis, ou les avatars d’un mythe du XVIe au XXe siècle,’ (in L. Bricault ed. De Memphis à Rome, 2000, pp. 163-188) provides a thorough academic overview of the process of this “reanimation” and its various avatars.

One of the more curious features of Court’s work, which lends a certain amount of credence to the foregoing speculation, is pointed out by Edelstein: “Court’s insistence on the sun and the moon as perfect divine symbols cannot (to my knowledge) be traced back to any prior text, and is not explicitly addressed in the work itself. Their privileged status may be explained by the centrality of the sun and the moon in Masonic culture and practice.” (op. cit. p.222) Indeed, neither Macrobius, who insists on the centrality of the sun, nor Plutarch, who penned an essay entitled De Facie in Orbe Lunæ, report any such dualism.

Further considerations of this type lie beyond the scope of the present introduction, suffice to say that the use of myth, in this respect, could be examined more closely in the Sorelian perspective, to name but one, in addition to that of Lévi-Strauss.

The ultimately socio-political nature of Court de Gébelin’s enterprise is further underscored by Sophia Rosenfeld, who writes that:

“many of the initial members of the Loge des Neuf Soeurs […] manifested a profound interest in prescriptive language planning and semiotic experimentation, moving away from “usage” or “custom” toward an historic notion of “nature” or “reason” as a guideline. Furthermore, the members of this latter group tended to see their plans for improved communication as efforts on behalf of the good of the public as a whole. Indeed, some even argued that rational language reform would ultimately be instrumental in bringing about cognitive and, consequently, social and moral transformations in the future.

Especially important in this regard was the work of Antoine Court de Gébelin, whose home has become the meeting place for the lodge beginning in 1778. Throughout the decade of the 1770s, in a series of massive volumes entitled Le Monde primitif analysé et comparé avec le monde moderne, Court de Gébelin had set about trying to rediscover and to catalogue the original, universal mother tongue, the collection of radical sounds and images he took to be given by and representative of nature – or, in Genette’s terms, “mimological” – rather than arbitrary. […] But it is important note that what drove Court de Gébelin in this quest was not simply antiquarianism or a fascination with the burgeoning field of comparative linguistics. The physiocratic philosopher believed that the discovery and reconstruction of this original idiom, or protolanguage, would allow modern men nothing less than a chance to uncover the timeless, natural laws governing human happiness, and thereby to restore peace and prosperity on earth. For Court de Gébelin insisted that this lost knowledge, both visual and aural, would provide the key to the construction of a superior, modern language, one which would aid in restoring the purity and perfection of an earlier golden age in which people communicated without impediment and easily realised their common bonds.” (Sophia Rosenfeld, A Revolution in Language: The Problem of Signs in Late Eighteenth-Century France, Stanford University Press, 2001, pp. 113-116)

Baltrušaitis’s concluding remarks are worth reproducing: Egypt, he states, “remains always a composite of singularities, of paradoxes, of rigid reasonings and of poetic falsifications… […] The legend of the Egyptian myth is not only the nostalgia of a Paradise Lost. It is also the implacable logic that rubs shoulders with unreason, and an erudition placed in the service of dreams. The whole belongs to a chapter of the history of human thought gone astray.” (op. cit., p. 321.)

These dreams, as Anne-Marie Mercier-Faivre has demonstrated in her article, ‘Le Langage d’Images de Court de Gébelin’ in Politica Hermetica vol. 11, are “a dream of return to a (mythical) past which would become a reality. For Court de Gébelin, it is not only a matter of giving a reading of the symbolism and language of the ancient world, but also of reforming the modern world. … It is not a matter of doing archaeological research by deciphering symbols, but of changing the relationship of modern man to his language, and thereby to the world and to time.” (p. 53)

First published Dies Natalis Solis Invicti 2020 e.v.

Revised Imbolc 2023 e.v.

***

- Read the article The Isis of the Tarot, or the Birth of a Myth.